Line between devices and cloud services fades as online storage allows users to switch without losing data by Craig Timberg for the Washington Post

After security researcher Jeffrey Paul upgraded the operating system on his MacBook Pro last week, he discovered that several of his personal files had found a new home – on the cloud. The computer had saved the files, which Paul thought resided only on his own encrypted hard drive, to a remote server that Apple controls.

“This is unacceptable,” thundered Paul, an American based in Berlin, on his personal blog a few days later. “Apple has taken local files on my computer not stored in iCloud and silently and without my permission uploaded them to their servers – across all applications, Apple and otherwise.”

He was not alone in either his frustration or surprise. Johns Hopkins University cryptographer Matthew Green tweeted his dismay after realising that some private notes had found their way to iCloud. Bruce Schneier, another prominent cryptography expert, wrote a blog post calling the automatic saving function “both dangerous and poorly documented” by Apple.

The criticism was all the more notable because its target, Apple, had just enjoyed weeks of applause within the computer security community for releasing a bold new form of smartphone encryption capable of thwarting government searches – even when police have warrants. Yet here was an awkward flip side: police still can gain access to files stored on cloud services, and Apple seemed determined to migrate more and more data to them.

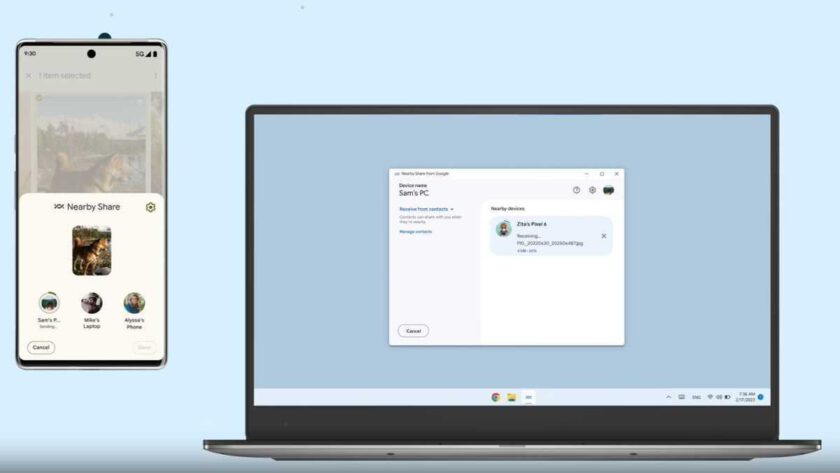

The once-clear line between devices – such as Macs or iPhones – and proprietary cloud services is all but vanishing, security experts warn. And it isn’t just Apple doing it. Microsoft, Google and others are increasingly relying on cheap, easily accessible storage capacity to roll out new features for customers. Apple’s automatic saving function allows users to switch seamlessly between devices, without fear of losing documents or edits.

That’s great news if your Mac gets stolen and you need to buy a new one. But security experts such as Paul are asking, at what price in privacy?

“For me,” said Green in an interview, “this is really shocking. I’ve been taking a lot of confidential notes in business meetings in TextEdit” – one of the programs that automatically saves some files to iCloud.

Confusion about how devices and cloud services interact was apparently a factor in the theft of intimate photos of dozens of Hollywood celebrities, such as Jennifer Lawrence, this summer. Their phones were secure, but the photos were also stored in online Apple accounts that, while protected by passwords, were vulnerable to hackers, experts say. It’s not clear that the victims had any idea their personal photos were in the cloud, but they were – within the reach of highly skilled internet creeps.

Paul’s concern is less about freelance internet creeps than it is about the US government, which, as he noted in his blog post, collects data from US technology companies, including Apple, through the National Security Agency’s Prism programme.

The US supreme court ruled in June that mobile phones deserve a high level of protection from police searches, requiring in most cases that a court find probable cause and issue a warrant seeking specific evidence. But the issue is less clear when it comes to information found on cloud services; many companies require warrants, but no definitive legal standard has yet emerged for law enforcement access to such information.

As for the NSA and the other hi-tech intelligence operations run by governments around the world, the revelations by Edward Snowden make it clear that government hackers are ingenious and voracious. And while the best can probably hack their way into any individual phone – even those with the tougher, new encryption offered by Apple – experts say it’s easier to collect data on a mass scale when it’s housed in centralised locations, such as on company cloud servers.

Apple did not reply to a request for comment about Paul’s blog post or the issues he raised, but it has published a document on its website describing how the automatic-saving function works. The gist is that files created on several widely used apps are saved to iCloud as soon as they are created. When a user later gives the file a name and selects a location to store it, the document is “removed” from iCloud (unless, of course, the user intentionally saves the file to iCloud). Users can also disable iCloud altogether, keeping files confined to their devices.

But it turns out that many people use these apps without immediately naming documents or designating a place they should be saved. Green, the Johns Hopkins cryptographer, long has used TextEdit as an easy way to take notes that he thought were safe on his hard drive, only later giving them a file name. Paul used the same program to jot down other information, including passwords, private information, even the occasional love letter.

By the time he discovered the files were being uploaded to iCloud, the deed was already done. Paul said he could recall no warning that iCloud would operate in this way.

As his blog post bounced around the Web, other researchers discovered another twist to the Mac’s automatic iCloud save function; it didn’t arrive with Yosemite, the new operating system released last month. The support document Apple published on the subject was dated 16 December 2013. The automatic-saving function might go back even further – yet few seemed to notice its introduction.

Paul wrote in an email, “If you take 100 people and sit them down in front of a factory-new machine running Yosemite with iCloud Drive and have them open TextEdit, create a new window, type their darkest secrets into that window, and power the machine off without saving it anywhere – how many of those 100 would believe that the data hadn’t left the room?”

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from the Washington Post

Adapted from Guardian